Feb 12, 2025

TB, Mimì and Indigenous Peoples

Winnipeg opera and theatre performer Keely McPeek is a member of the Anisininew (Oji-Cree) Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation in northwestern Ontario with Irish and German settler roots. She made her MO debut as Marie Serpente in Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North in 2023 and sits on the Manitoba Opera Community Engagement Committee.

Winnipeg opera and theatre performer Keely McPeek is a member of the Anisininew (Oji-Cree) Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation in northwestern Ontario with Irish and German settler roots. She made her MO debut as Marie Serpente in Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North in 2023 and sits on the Manitoba Opera Community Engagement Committee.

In La Bohème, Mimì suffers from an infectious disease contracted by inhalation called tuberculosis (TB).1 Referred to as consumption at the time in which the opera is set, TB is depicted in the opera as a social disease that particularly impacts those living in poverty.2 Mimì suffers from malnutrition and inadequate living conditions, creating an ideal environment for tuberculosis and in the end, she wastes away and succumbs to the disease.3

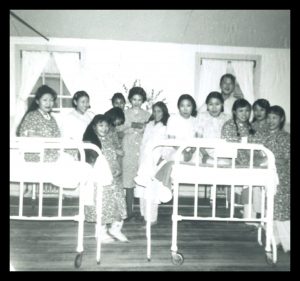

A group of young patients at Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital in 1964. This building was not intended for long-term use, leading to many structural issues. Image source: https://indigenoustbhistory.ca/projects/photos/will-01-39-001

A group of young patients at Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital in 1964. This building was not intended for long-term use, leading to many structural issues. Image source: https://indigenoustbhistory.ca/projects/photos/will-01-39-001

Tuberculosis has disproportionately affected Indigenous peoples in Canada since Europeans brought the disease in the 18th century.4 In the 1930s, the term “Indian TB” was coined to label a more virulent form of the disease that Indigenous peoples were thought to be more racially susceptible to.5 The “experts” who coined the term failed to consider the social aspects that caused higher TB rates in Indigenous populations, such as poverty, malnutrition, and overcrowded and inadequate housing on reserves and in residential schools.6 Indigenous peoples were deemed a public health threat, “soaked with tuberculosis,” which could “leak” into settler communities.7 In Manitoba’s response to the perceived threat of “Indian TB,” an “Indian Hospital” opened near Selkirk in the late 1930s.8 “Indian Hospitals” promised to segregate Indigenous peoples to contain TB while giving the impression of a humanitarian Canadian government.9 The care of Indigenous peoples was expected to cost half as much as the care given to non-Indigenous people.10 “Indian Hospitals” provided substandard medical care in overcrowded facilities that were ill-suited for proper care.11 Many patients experienced abuse from staff, were subjected to medical experiments, and were isolated from their communities.12 Indigenous peoples have suffered a long history of being disproportionately impacted by TB.

Tuberculosis is not a disease of the past; it still disproportionately affects Indigenous people.13 In 2023, Indigenous individuals accounted for 77% of new TB cases among the Canadian-born population.14 Manitoba has a higher incidence of tuberculosis compared to most provinces, falling behind only Nunavut and Saskatchewan in 2022.15

Poverty has been a risk factor for developing TB since before the time La Bohème was written. Indigenous peoples in Canada continue to face socio-economic disparities compared to the non-Indigenous population.16 Many Indigenous peoples today live with malnutrition and inadequate housing, increasing their risk for TB infection – these same risk factors which the seamstress Mimì confronted.17