Jun 26, 2024

Magical Elixirs, Medical Quackery & Snake-Oil Salesmen

In Donizetti’s The Elixir of Love, the titular tincture is procured by the naïve and lovesick Nemorino from the travelling physician Doctor Dulcamara. Nemorino, down to his last pennies and unlucky in love, approaches the self-styled “Encyclopedic Doctor” who entertains an audience of villagers. Dulcamara hawks medicines and salves to cure liver disease and paralysis, smooth wrinkles, eradicate lice and vermin, increase libido, and so on, haggling prices down from extravagantly unaffordable to taking whatever coin he is offered. Nemorino begs him for the love elixir of Queen Isolde. Although the doctor is unfamiliar with the tale of Tristan and Isolde, he nevertheless leaps at the opportunity to make a quick sale, exchanging the erstwhile magical liqueur – SPOILER ALERT – (actually a bottle of red wine) for the sum total of Nemorino’s wealth – a single zecchin (a Venetian ducat), and cautioning the young man that the elixir will require 24 hours to take its effect (giving the fraudulent doctor time enough to get out of town).

This kind of medical quackery is a familiar trope, being well-documented in histories and lampooned in works of fiction.

“The term quack originates from quacksalver, or kwakzalver, a Dutch word for a seller of nostrums, medical cures of dubious and secretive origins . . . they plied their trade on street corners and at country fairs, hawking homemade remedies in loud, attention-grabbing voices—hence the term quack, likening their cries to noisy ducks or geese.” – Drago, E. B, 2020.

Even the word “charlatan” is directly related to quackery. The word comes from “Cerretani,” the name for people from Cerreto di Spoleto- a small town in what is now Italy that became notorious in the Middle Ages for widespread fraud committed by its inhabitants who would collect alms on behalf of medical and religious foundations which they would keep for themselves. This evolved to medical charlatanism, exploiting the absence of institutional medicine in rural areas and the superstition of a poorly educated populace. There and across Europe, unscrupulous vendors sold cure-alls concocted from all manner of bizarre and potentially dangerous (or even wholly fictitious) components. One such prescription, published by Sr. William Solomon of London in the 17th century calls for:

Gold, one half ounce.

Powder of a lion’s heart, four ounces.

Filings of a unicorn’s horn, one half ounce.

Ashes of the whole chameleon, one and a half ounces.

Earthworms, a score.

Dried man’s brain, five ounces.

To be mixed together and digested with universal spirits.

Such practices were not isolated to Europe. A North American audience might draw parallels to the iconic snake-oil salesmen of the old West. The great irony of snake-oil is that it originated as a genuine product – an oil derived from Chinese water snakes, high in omega-3 fatty acids and known as a potent anti-inflammatory.

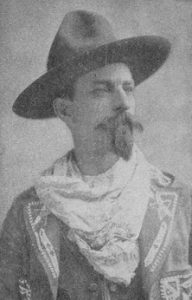

In the late 19th century the American Clark Stanley, a cowboy turned patent medicine vendor, learned about snake oil from Chinese railroad workers. He set about to capitalize on its reputation, unconcerned that Chinese water snakes were nowhere to be found in the American West. From 1879 the “Rattlesnake King” touted a miracle salve produced from rattlesnake oil, the secrets of which he claimed to have learned from a Hopi medicine man. He distributed pamphlets and gave public demonstrations to sell his patent-protected panacea which he prescribed:

“. . . for the cure of all pain and lameness, for rheumatism, neuralgias, sciatica, contracted muscles, toothaches, sprain, swellings, frost bite, bruises, sore throat, bites of animals, insects, and reptiles.” – Bryant, C.W. & Clark, J., 2024.

It wasn’t until 1916 that this “snake oil” was found to have nothing to do with snakes whatsoever – the recipe consisted of beef fat, red pepper, mineral oil, camphor, and turpentine. For his fraudulent activities spanning over three decades, Stanley was fined $20 (equivalent to about $500 today). The damage had been done, and “snake oil salesman” entered the public lexicon as an umbrella term for any person selling a bogus or ineffective product.

Works consulted:

Bryant, C. W. and Clark, J. (2024, February 14). Short Stuff: The Original Snake Oil Salesman. Stuff You Should Know (podcast). https://omny.fm/shows/stuff-you-should-know-1/short-stuff-the-original-snake-oil-salesman

Drago, Elisabeth Berry (2020, December 15). Quacks, Plagues and Pandemics: What charlatans of the past can teach us about the COVID-19 crisis. Distillations Magazine: Unexpected Stories from Science’s Past. Science History Institute Museum & Library, December 15, 2020. https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/quacks-plagues-and-pandemics/

Peschel, E. R. & Peschel, R. E. (1987, December). Medicine and Opera: The Quack in History and Donizetti’s Dr. Dulcamara. Medical Problems of Performing Artists Vol. 2, No. 4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45440260

Timio, M. (2002, February) “The Cerretani and charlatans: a poor page in the history of medicine and nephrology” (abstract, English). Giornale Italiano di nefrologia : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana de nefrologia. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12165947/

View Media Release