Sep 26, 2023

By Nicole Stonyk, with mention and gratitude to Jennine Krauchi and Sherry Farrell-Racette

Indigenous beadwork is a significant component of cultural expression. After falling out of predominance due to various factors including cultural loss through residential and day schools, disenfranchisement, displacement and racism, beadwork is now seeing a resurgence amongst contemporary artists.

In conversation with Jennine Krauchi, Métis bead artist, she noted it was not long ago that only a few people would be seen beading around a table, and now you can fill entire halls! This resurgence illuminates not only the aesthetic art form itself, but importantly its (re)connection to story, relationships, healing, and joy.

Beadwork is a central component of historical Métis culture and served as a commercial economy for Métis women, but it also represents the story of a collective community, identity, expressed love, gift-giving, and social visibility.

There are a variety of beadwork styles and patterns that are related towards various Indigenous nations, and many share the five-petal floral pattern. However, Métis floral patterns are different in style than Cree or Ojibwe and are distinct through the infusion of French embroidery. A marked feature of Métis-style floral patterns is the accompaniment of “mouse tracks.”

Krauchi notes there is a lot of love and joy that is put into beadwork and that nothing else quite signifies Métis culture more than beadwork. In fact, when creating a piece, you must have “good thoughts” and think of who you are beading for with each bead sewn. Without good thoughts, it will show in the work which will have to be undone the next day! Krauchi notes that not every piece of beadwork tells a specific story, but that it is a connection between the maker and the beadwork itself. It could simply be for the pure enjoyment. Beadwork is also a personal style in which the maker becomes apparent through observing the design and beading pattern.

Sherry Farrell-Racette, interdisciplinary Métis scholar in the arts, discusses recentering the voices of women and their stories through material culture in her dissertation, “Sewing Ourselves Together” (2004). Farrell-Racette demonstrates how beadwork was used to represent the daily lives of Métis people that linked the hands and hearts of women and was also a communal effort involving a high level of intergenerational skill. However, beadwork exists not only in a historical past, but is an important part of contemporary cultural resurgence amongst contemporary artists. These artists consider their work deeply meaningful and have found joy and healing through the process of carefully designing a work, selecting the colours, the bead-type, and the act of beading itself.

Two types of contemporary, but historically inspired beadwork pieces are the Tapis and Fire Bag. These pieces will be displayed in Li Keur along with many other beadwork pieces from the grandmothers.

Fire and Octopus Bags

Historical beadwork functioned for aesthetic value and was also used on everyday items. The Fire Bag is an example of a daily essential item for life and travel in the 19th century. It was used to carried flint, a steel striker, and other items needed to start a fire. The earliest Fire Bags sewn and used by Métis were primarily Saulteaux-inspired and illustrate the close cultural and kin connections they had with each other.

The Fire Bag became a more distinct Métis style as they were embellished with various new materials and trade goods – some of which, given the style of beadwork and materials used, can determine the region it came from or who might have beaded the bag. The Fire Bags that are commonly displayed in museums are called “Octopus” bags given their eight long tabs, or “fingers.” The Octopus Bag provided form, function, and an aesthetic medium for individual expression and are known for their vibrant colour and decorative beadwork.

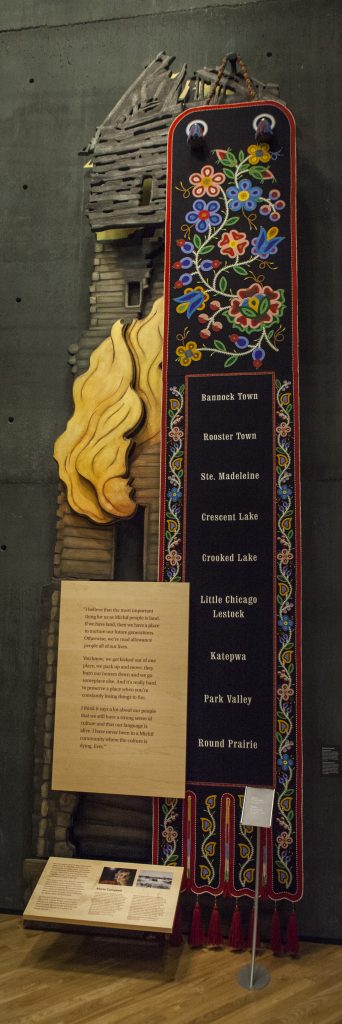

This particular Octopus Bag, created by Jennine Krauchi alongside her mother, Jenny Meyer, is considered the largest Métis beaded art piece in the world. It stands at over seven metres tall and weighs nearly 60 pounds. The design was beaded mainly using antique beads from the fur-trade era, but most importantly, the design features nine Métis flowers to represent nine Métis villages that were deliberately burned or destroyed to clear land for colonial expansion. The communities listed on the Octopus Bag are Ste. Madeline, Bannock Town, Crescent Lake, Crooked Lake, Little Chicago Lestock, Katepwa, Park Valley, Round Prairie, and Rooster Town. Many of the displaced Métis families from these communities, along with others, were forced further into diaspora. For Jennine, the large-beaded rose on this piece represents the survival of the Métis people.

Watch for the “real life size” replica of the Octopus Bag in Li Keur!

The Tapis or Tuppee

Red River buffalo brigades were found everywhere on the prairies during the 19th century and are featured in the story work of Li Keur. In addition to the buffalo brigades of the 19th century, there were also cart drivers used for transport of freight goods throughout the homelands.

In winter months the cart drivers turned towards winter transport and used a team of sled dogs that were the “athletes of their day.” Some of these teams averaged nearly 56 kilometers per day. The sled dogs of the Métis were the pride of their drivers and wore the Tapis, also known as a Tuppee, made with wool or felt blankets with elaborate floral designs decorated with fringe, ribbons, and bells. If you listen carefully, you can “hear” the bells of the Métis sled dogs and their Tupis in Li Keur!

It was a celebration when the teams returned home from trapping or trading posts, and just before the drivers glided into town, they decorated their dogs, sleds, and themselves. The decoration was also used to show status. If trapping or trading was successful, it showed a good provider who brought in the best furs and beads.

Some of the beadwork displayed 25-30 different colours as more beads and colour was an indicator of love. Interestingly, Métis women, who beaded for their love of family, others they cared for, their dogs, and even horses with beaded pad saddles, rarely wore beadwork themselves.

Li Keur features many other beaded pieces that show the work of the grandmothers. Incorporating the grandmothers’ work connects their hand and hearts to contemporary audiences and contributes to Li Keur’s overall theme of re-centering women, celebration, and love. It also gives a sense of the cultural milieu that encompassed the heart of the continent in the mid 19th century. As well, it connects the aesthetic visual and story work of Li Keur that centres collective identities of women and as a metaphoric means to “stitch ourselves together.”